Getting past John Key’s ego and changing the superannuation age

I remember during my first year of university study being introduced by lecturer John Henderson to Dr James Barber’s typology of American presidents according to their character and worldview. Dr Barber’s work assessed presidents on two baselines.

- The amount of energy they invested in their presidency (active vs passive)

- How much they seemed to enjoy their political life and work (positive vs negative)

Although Dr Barber’s breakdown of leadership styles has been criticised as being overly simplistic, it still provides some insight into why leaders behave the way they do. Mr Henderson stated in his 2006 assessment of New Zealand prime ministers’ personalities and styles, that “Barber saw ‘active positive’ as the most desirable leaders as, in contrast to the ‘active negative’ type, they are able to separate their political goals from personal ego needs.”

Barry Gustafson stated it another way in his biography of Robert Muldoon, saying that the active-positive leaders “are often the achievers who are free from self-centred inner demands that prevent rational decisions and who make choices that can be altruistic and not limited by personal needs.” Popularity, or the desire to be liked, is not an end in itself, but simply a means to furthering policies that the leader believes are good for the country. Similarly, a desire for power is not a goal on its own.

In contrast, Robert Muldoon was an active-negative Prime Minister – hard-working and focused on politics, but also aggressive and distrusting of others. The fact that he spent the last seven years of his parliamentary life sniping from the backbenches at both the Labour Party and his National colleagues highlights the negative characteristics of his personality.

Despite Russel Norman’s assertion over the weekend that John Key is “acting like Muldoon”, Mr Key can best be typified as an active-positive leader, following a string of leaders with similar styles stretching back to Jim Bolger in the 1990s. Where he perhaps differs from other leaders of a similar ilk is that he is not a career politician. From the time he first entered parliament, his rise to both National Party leader and prime minister was more rapid than any previous prime ministers. Whether you agree with his policies or not, he gives the impression that his political raison d’être is to get into power, do what he believes is best for the country, and get out again. He is unlikely to stay in parliament once his time as prime minister comes to an end.

But if there’s one area where Mr Key’s decision-making seems to have become derailed, it’s in the area of superannuation. In the lead-up to the 2008 election, he pledged that he would resign as prime minister and an MP if there were any changes to superannuation entitlements and eligibility, and he has stood by that promise ever since. His intransigence has remained despite long-term projections from Treasury showing a looming blow-out in the superannuation bill and fiscal deficit, a report from the Retirement Commission in 2010 recommending a two-year lift in the retirement age between 2020 and 2033, pressure from across the political spectrum to consider possible options for change, and a number of polls showing popular support for lifting the retirement age.

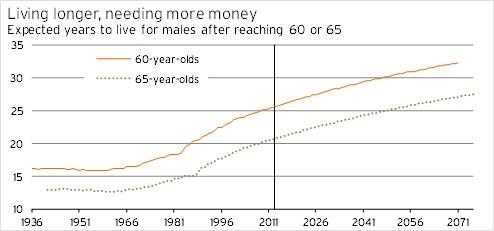

The fiscal cost of the aging population, in terms of both health and superannuation spending, is the most critical long-term issue facing policymakers. For whatever reason, John Key seems to have tied his colours to the wrong mast and is steadfastly refusing to admit his mistake. Our graph below shows the average life expectancy over time for 60 and 65-year-old males. The most important point to note from this table is that 65-year-olds are now expected to live almost five years longer than 60-year-olds were in 1938 when the age of eligibility for old-age pensions was first set at 60 (albeit means-tested below age 65 until 1977). In other words, increasing life expectancies with no change in the retirement age mean that people will be supported by the state for longer, despite health advances meaning that they will generally be able to work for longer and thus not need state support until later in life.

Graph 1

Originally, back in 1898, old-age pensions in New Zealand were designed to provide a safety-net for people with little wealth who were considered too old to work. That targeting has disappeared, with superannuation now providing a minimum level of income for all people aged over 65. The public has shown little appetite for any return to means testing, so assuming no changes in this area, it seems sensible to consider the age of eligibility instead. The reality is that medical advances have extended people’s total lifespan, their potential working life, and the health quality of life in their latter years.

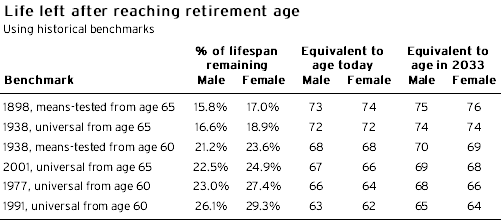

Table 1

When the first means-tested old-age pension was introduced in New Zealand in 1898, the average life expectancy for 65-year-olds was 12.2 years for males and 13.3 years for females, or 15.8% and 17.0% of their lifespans respectively. Our table applies this benchmark and others to life expectancies currently and in 2033.

The numbers are clear. If we rule out eligibility in 1991 (prior to the lift in retirement age from 60 to 65) as being too generous, the current retirement age of 65 is too low by historical standards. The older benchmarks, such as in 1898, are arguably not generous enough – nobody is advocating a retirement age of 75. But the middle two rows of the table suggest that the retirement age should already be around 67, and could realistically be as high as 70 by 2033.

Back in 2010, John Key said that “for a variety of reasons but in my view, New Zealand super is sustainable at age 65”, flying in the face of virtually all the evidence. His standpoint is the biggest impediment to changes to the retirement age. A lift in the retirement age at some point in the future seems virtually inevitable, but the shift is not about depriving current or imminent retirees of their anticipated entitlements. Instead, the government should be clearly signalling the move well in advance to give people who are 10-15 years away from retirement the opportunity to adjust their expectations about how long they will need to keep working.

If Mr Key is genuinely interested in what’s good for the future of the country, and is an active-positive leader whose decision-making is not dominated by his own ego, he would recognise his mistake about the retirement age and stand down. There are plenty of others within the National caucus who could maintain the Party’s broader policy focus while successfully navigating their way past the stumbling block of the retirement age.