New Zealand to outperform Aussie?

As China rebalances towards more of a focus on consumption-led growth, New Zealand’s terms of trade is likely to remain at an elevated level, while Australia’s terms of trade will come under downward pressure. As a result, we anticipate that the New Zealand economy will outperform its Australian counterpart over the forecast horizon.

China’s economic growth over recent decades has been characterised by robust growth in manufactured goods exports and high levels of investment in capital equipment. Recently, however, the Chinese Communist Party has begun to switch tack towards promoting domestic consumption as a more dominant driver of growth. These policy choices made in Beijing will not only slow overall growth in China, but will reduce growth in economic activity in other Southeast Asian nations that contribute to the Chinese supply chain. Why and how this change is occurring is discussed in more detail in Asian rebalancing: good, or a necessary evil?.

With economic growth in China and many parts of Southeast Asia slowing, policymakers in New Zealand and Australia have understandably become nervous regarding the effect these changes will have on our economies. But rather than getting too bogged down looking at headline growth figures, it is also important to understand what factors are driving this shift in China’s growth trajectory.

The switch from investment to consumption-led growth is substantially affecting China’s resource demand, with demand for hard commodities falling, while demand for agricultural goods continues to climb. These changing demand patterns have caused a significant divergence between different types of commodity prices over the past year. The prices of New Zealand’s agricultural goods (which are consumption goods) have risen, while the prices of Australia’s hard commodities (which act as an input to manufacturing and investment goods) have fallen.

This article discusses the recent history and outlook for Australia’s and New Zealand’s terms of trade indices (ratio of export to import prices) in turn, before concluding by discussing how this expected outlook for export prices will affect the relative levels of economic activity between our two nations.

Australia’s terms of trade has fallen – but is still historically elevated

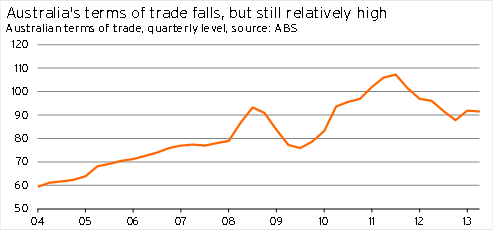

Australia’s terms of trade index soared throughout much of the past decade, as rising investment and manufacturing-driven growth in China pushed up demand (and prices) for hard commodities. At the same time, import prices were kept in check by a combination of technological advancement, Chinese subsides, and a low fixed exchange rate for the Chinese renminbi, which was supported by high levels of Chinese savings. By September 2011, Australia’s terms of trade had reached 107.2 (see Graph 5.4), compared with a level of just over 50 at the turn of the century.

However, since late 2011, Australia’s terms of trade has eased once more, as Chinese authorities have begun to encourage a transition away from an investment-led growth model. In the June 2013 quarter, Australia’s terms of trade was 15% below its September 2011 peak. Even so, Australia’s terms of trade remains elevated compared to historical levels, sitting some 50% above its 50-year average and 13% above its decade-long average.

The key contributor to the recent weakness in Australia’s terms of trade has been falling mineral commodity prices. World spot prices for iron ore peaked at around US$187/tonne in February 2011, but by August 2013 had fallen to US$137/tonne. World spot prices for Australian thermal coal tell a similar story, tumbling from US$142/tonne in January 2011 to US$82/tonne by August. According to information from the Reserve Bank of Australia, these trends continued into September, with world prices gleaned from export data showing that iron ore and coal prices fell another 0.8% in the month.

Graph 5.4

Looking ahead, forecasts from the RBA and major Australian banks show that a further 5-10% easing of Australia’s terms of trade index is expected over the next 18 months. This easing will be caused by a further weakening of mineral demand relative to the global supply capacity for these resources.

Even if the terms of trade falls a further 10%, this result would not be a bad one – the index would still be on par with its ten-year average. However, it does suggest that the golden age for the lucky country is coming to an end.

Over the longer-term, Australia is likely to suffer from more rapid import price growth, as China’s shift towards consumption-led growth and greater equality will push up input costs, such as wages, in China. The Chinese government will also allow the Chinese renminbi to appreciate further, which will remove one part of the subsidy that, in the past, has promoted excessive investment into export-orientated industries.

Although these factors will result in more rapid increases to import prices for Chinese manufactured goods, rising demand for mineral commodities from other parts of the developing world will help minimise any further long-term downward pressure on Australia’s terms of trade. As a result, we would still expect Australia’s terms of trade to eventually settle at a level which is not far below its recent ten-year average.

New Zealand’s terms of trade pushing back to record levels

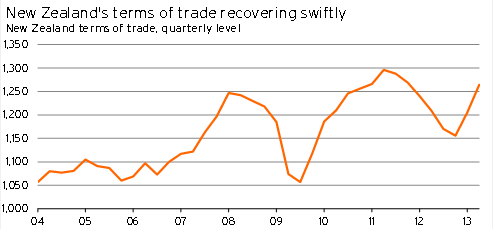

New Zealand’s terms of trade has also increased substantially over the past decade, although compared to Australia, these gains occurred later, and the magnitude of the uplift to date has been more modest. The reason for the more sluggish response in New Zealand’s trade fortunes was that Australia’s export commodities were essential for even the early stages of China’s investment push, whereas demand for New Zealand’s key agricultural export commodities only began to rise as wealth and consumption in China grew thereafter. The signing of a free-trade agreement with China, which came into force in 2008, has also encouraged more demand for New Zealand goods.

Having declined throughout 2012, New Zealand’s terms of trade has begun to recover rapidly, as dairy prices soar, forestry prices pick up, and most other key commodity prices stabilise. By June 2013, the index had closed to within 2.5% of its June 2011 peak. At this level, New Zealand’s terms of trade is more than 23% above its 50-year average and 9.3% above its decade-long average.

Graph 5.5

We anticipate that New Zealand’s terms of trade will continue rising over coming quarters and by March 2014 will have pushed back to a record high. The key driver of this lift will be dairy prices, which remain at an extremely elevated level, as the lift in global demand for dairy products exceeds the recovery in domestic supply following the drought. Prices for other key agricultural commodities, such as horticultural goods, meat, and wool also appear to be stabilising, while wine prices are recovering from a low base.

The only one of New Zealand’s key export commodities whose outlook appears grim is aluminium. Export prices for aluminium fell by 5.4% over the past year, pushed down by high levels of new supply in China and Japan, coupled with a more modest outlook for Chinese demand. As China continues to transition towards more consumption-led growth, it is likely that aluminium prices will remain subdued over the forecast horizon.

The outlook for forestry prices, a good more typically associated with investment-led growth, remains healthy. The reason for this positive outlook is due to expectations of rising demand for timber in the US, which is pushing up global forestry demand. These issues are dealt with in more detail in Drivers of upturn in forestry industry lie beyond China.

Over the longer term, we expect New Zealand’s terms of trade to settle back to within spitting distance of its current level – around the 1,250 mark. Although New Zealand’s import prices will rise more rapidly as Chinese manufactured goods prices pick up, New Zealand’s exporters will continue to benefit from rising consumption and discretionary income among Chinese households. Not only do we anticipate that demand for dairy, meat, and other horticultural products in general will rise, but exporters’ ability to sell higher-value products and cuts of meat will also improve.

Comparing the Trans-Tasman neighbours’ outlooks

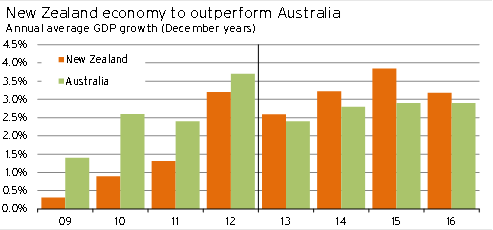

With regards to the relative outlooks for the New Zealand and Australian economies, the above discussion essentially boils down to a single conclusion. Although both countries will face higher import costs, Australia will receive lower prices for its hard commodity exports, while the prices of New Zealand’s agricultural exports are likely to be buoyed by increased consumption demand in China. In other words, the changes in the composition of Chinese demand are causing the relative performance of New Zealand’s and Australia’s terms of trade indices to shift in New Zealand’s favour.

Not surprisingly, this improvement in New Zealand’s trade outlook compared to Australia’s has contributed to a significant shift in our outlook for the relative economic performances of these two nations. Over the next four years, we expect the New Zealand economy to outperform its Australian counterpart, growing by an average of 3.2%pa, compared with 2.8%pa for the Australian economy.

Graph 5.6

With the Australian economy performing slightly below trend, Australia’s unemployment rate is expected to rise to 6.2% by March 2014, at which point New Zealand’s unemployment rate should have fallen below 6%. We also expect this relative underperformance of the Australian labour market to drive a significant lift in New Zealand’s net migration over the next few years, as fewer New Zealanders decide to chase their fortunes across the Tasman and increased numbers of people choose to return home.