Agricultural competition from Australia?

A series of droughts, the mining boom, and the high Australian dollar had made it seem like Australia and New Zealand were no longer competing in agricultural export markets. However, with the mining boom falling flat and the Aussie dollar falling, the potential for increasing competition for the Chinese market is on the cards. So how does Australian agriculture look, and how far will they go in undermining New Zealand’s return from trading with China?

The Australian dollar and weather conspire against soft commodities

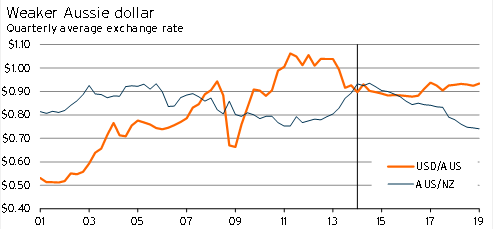

After declining to low levels at the end of 2001, the Australian dollar starting a long march upward against the US dollar. Between the December 2001 quarter and June 2011, the Australian dollar appreciated 108% against the US dollar (more than doubling in value).

Between March 2011 and March 2013, the quarterly average for the Australian dollar was above parity with the US dollar – a significant period of strength in the currency. Behind this strength was the relatively good performance of the Australian economy and the high prices received by hard commodity exporters (eg copper and iron ore) who sold to China.

The strength of the Australian dollar is demonstrated by comparing what it costs to buy the same bundle of goods in different currencies – the exchange rate this suggests is called the purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rate. In PPP terms, the Australian dollar would be expected to be worth US68c, but between 2007 and today it was worth an average of US92c – including a period between February 2011 and May 2013 when the Australian dollar was valued (almost) consistently more highly than the US dollar.

In terms of soft commodities (eg dairy, meat, wool) exports, the high exchange rate has been a curse, as it has driven down the price received by exporters of these commodities.

Adding to this price pressure has been the drought (and flooding) conditions over recent years experienced in large parts of the country. This negative string of events appeared to have its biggest effect in 2010/11.

However, the changing focus of Chinese policymakers over the past year has had a significant negative effect on the price received by Australian hard commodity exporters. This shift has led to a sharp drop in the Australian dollar, which depreciated by 14% in the year to March 2014.

As a result, the recent combination of rising Chinese demand for soft commodities, more stable weather conditions, and the sharp drop in the value of the Australian dollar has significantly improved the competitiveness of the Australian agricultural industry.

It is important not to overstate the effect of the lower Australian dollar. Lower hard commodity prices will ensure that the Aussie dollar remains well below its 2010-2013 levels against the US dollar, thereby increasing returns.

However, relative to the New Zealand dollar, Australia’s new found competitiveness due to the exchange rate is expected to start reversing out during 2015. Following the peak in the Canterbury rebuild there will be downward pressure on the New Zealand currency, helping to restore the competitive edge of New Zealand farmers.

Graph 5.1

Australia’s dairy push

Dairy is the main area where competition from Australia is expected to climb in the coming years.

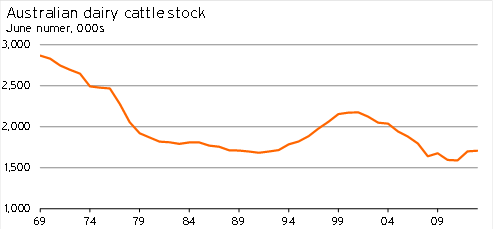

The size of the Australian dairy stock has been in decline since at least the 1960s (see Graph 5.2).

Graph 5.2

This decline has seen a significant change in the relative size of the dairy industries in the New Zealand and Australian economies. In 2006, Australian farmgate milk production was about 68% of production in New Zealand. With output falling in Australia, and rising by over one third in New Zealand, relative output in Australia had declined to 48% in 2012. In terms of final dairy products, the general trend of rising relative production held for most products (milk powder, butter, and skim milk), although Australian cheese production remains above New Zealand’s.

For the future of the industry in Australia, there is an increasing focus on China. To quote a Dairy Australia report:

China is now the world’s largest dairy importing country. It imported 1.375 million tonnes of dairy products in 2012, 47% from New Zealand. New Zealand’s FTA with China gives it a clear commercial advantage. It supplied more than 650,000 tonnes of dairy product to mainland China in 2012. By comparison Australia supplied just over 61,000 tonnes. Despite this scenario Chinese customers have occasionally expressed concern about being reliant on a single supplier. This risk management aspect could potentially bene?t Australian dairy exporters.

Chinese investment in Australian dairy, and negotiations around the trade status of Australian dairy products, began in late 2012. However, it wasn’t until early this year that a key breakthrough in negotiations occurred – with Chinese officials agreeing to cut the quarantine time on Australian dairy exports from 2-3 weeks to 8-9 days.

This change is expected to provide a boon to fresh and condensed milk exports from Australia to China – and, indeed, the latest figures suggest this boost to Australian exports is occurring. But while a lot of attention has been given to these changes, they are small in the grand scheme of things. Fresh and condensed milk exports from Australia only account for 12% of their total dairy exports.

Currently, Japan is the main destination for Australian dairy exports, and the focus of the Australian dairy industry had been to make inroads into China and take advantage of a Japanese-Australian free-trade agreement (FTA) to increase their presence in Japan further. The Japanese market mainly demands Australian cheese, with Japan taking 53% of Australia’s cheese exports – where total cheese exports account for 42% of Australia’s total dairy exports.

However, the Australia-Japan FTA that was agreed upon in April did very little to reduce export barriers to dairy exporters in Australia, providing further impetus for the industry to focus on China as an export destination.

Another area that will be important for Australian entry into the dairy market will be Chinese investment. Australia, like New Zealand, is part of a supply chain serving Chinese customers. As a result, Chinese investment in the supply chain is a logical step – and is ultimately in the interest of both nations involved.

After the Chinese Investment Corporation (CIC) became interested in investing in Van Diemen's Land Company in 2012, there was significant political and local resistance. By February 2014, the CIC decided to walk away from the deal, which was going nowhere. This breakdown occurred during a period when Fonterra was sharply increasing its acquisitions in Australia, without the slightest concern from the Australian government.

Australia’s foreign direct investment (FDI) laws are relatively restrictive, but the biggest issue actually comes from the fact that the laws are politically driven. As a result, outcomes are often based on non-fundamental characteristics, such as the nationality of the investors.

Although some Chinese investment has been able to take place, Australia is heavily constraining the ability for investment in their dairy industry – a relatively positive factor for the New Zealand dairy industry.

All in all, we have reached the following conclusions about the competitive risk that Australia poses for New Zealand’s dairy sector.

- The significant decline in the Australian dollar has made the Australian dairy industry more competitive. With the Australian dollar expected to stay well below its peak values, as China cuts back demand for Australia’s hard commodity exports, this new competitiveness will last.

- The Australian industry is strongly interested in increasing its exposure to China and believes that China is more than willing to diversify its suppliers.

- Recent announcements have improved Australia’s ability to enter and provide fresh and condensed milk.

- The disappointing Japanese FTA has limited the scope for further growth in the Japanese market – a market where sales were focused on cheese.

- Chinese investment in milk powder production in Australia is starting to take place, although Australia’s FDI laws are having a significant effect in terms of limiting the amount of investment coming through.

In the medium term, Australia’s ability to compete with New Zealand in the global, and specifically Chinese, dairy market depends upon its ability to switch production towards milk powder, and whether farmers have the incentive to rebuild dairy cow stocks (especially given the relative scarcity of water in Australia, which makes dairy farming relatively more expensive).

However, as long as Australia remains closed off to Chinese investment, its ability to undermine New Zealand’s position in China’s milk market is limited.

Australian bovine and sheep meat

Competition for beef and lamb exports to China looks like a significantly smaller issue. The value of bovine meat exports accounted for 2.2% of New Zealand’s exports to China in the April year ($182m), while sheep meat accounted for 9.5% of exports ($803m).

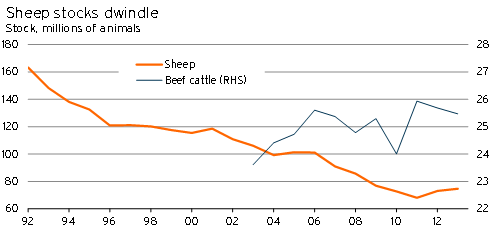

However, compared to the dairy industry, Australia has had more success at entering China for bovine and sheep exports over the past two years. In the June 2012 year, Australia exported 7.7kt (kilotonnes) of beef and veal to China, and by June 2013, this figure had risen to 92.3kt. During this period, lamb and mutton exports more than doubled – rising from 31.1kt to 69.9kt.

In fact, both New Zealand and Australia have experienced a lift in bovine and sheep meat exports to China since mid-2012. Prior to this point, rising protein demand by China had primarily been provided through rising dairy exports. As a result, even though bovine and sheep meat imports in China are rising, Chinese imports are still very low relative to other major markets.

Graph 5.3

The high Australian dollar and generally less supportive prices have seen slaughter rates and stocks fall significantly in Australia for sheep. Beef stocks have been relatively more stable.

Although both Australia and New Zealand are positioned to increase bovine and sheep meat sales to China, the situation is very different to that of dairy.

Unlike the dairy situation, there is not a concerted industry focus in Australia at knocking New Zealand off its perch. The meat market in China is also significantly less mature than the dairy market. Furthermore, unlike dairy, New Zealand’s exposure to China is smaller. Even after increasing fourfold in the past two years, New Zealand’s exports to China still only make up only 18% of total meat exports by value.

As a result, rather than being strict competitors, meat exports are still a major area for potential growth for both countries going forward.

Conclusion

The recent drop in the Australian dollar, and a concerted focus by the Australian dairy industry to knock New Zealand off its perch in China, offers a real threat to the returns of New Zealand dairy exporters. However, with Australia relatively unwilling to allow Chinese investment in their dairy industry, and with Australian dairy cow stocks having fallen in recent years, Australia’s ability to cut into New Zealand’s pre-eminent position is limited.

Although a lower dollar will also help Australia boost exports of bovine and sheep meat to Australia, meat exports to China appear to be an open growth area. As a result, there is plenty of scope for both nations to leverage off their clean green reputations to get a foothold in the Chinese meat marketplace.

In the medium term, Australia will remain more competitive in the agricultural industry than it has been in the past relative to most nations. However, the close relationship between Australia and New Zealand will also see the New Zealand dollar head lower, ensuring that New Zealand farmers can maintain their relative edge.

The biggest risk to the New Zealand dairy industry is that Australia changes its policy settings around foreign direct investment. If Australia becomes more willing to use direct investment to link its agricultural industry to the broad South Asian food supply chain, then there would be downward pressure on the price that dairy and meat manufacturers in New Zealand would receive.