Explaining the gender pay gap

In recent decades , a narrowing has occurred between men’s and women’s labour force participation, paid hours of work, hours of work at home, life-time labour force experience, occupations, and education. Indeed, young women are now obtaining qualifications at a higher rate than men. Yet despite an observed convergence in earnings, a gap between the wages earned by men and women still persists.

A recent paper by Claudia Goldin provides some interesting insights into the reasons why a gender wage gap persists. Her analysis is based on the US, but many of her observations are likely to also apply in New Zealand.

Over the years a number of theories have been proposed for explaining the existence of a gender wage gap. These include:

- Discrimination

- Underlying differences between the human capital capabilities of men and women

- Women’s lower ability or preference to bargain and compete in the work environment

- Differential promotion standards due to perceived gender differences in the probability of leaving

- Gender based occupational segregation that results in female workers being clustered in lower paying occupations.

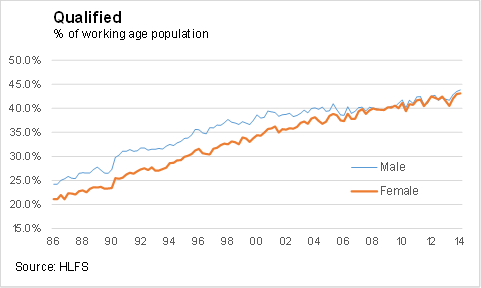

Although each of these explanations may have contributed to historical wage differences, Goldin argues that they are not convincing explanations for the persistence in the gender pay gap. One can never fully discount the presence of discrimination, but there are at least statutory protections against discrimination in the labour market. The growth in female qualification attainment has reached a point where, at least in aggregate terms, there is no obvious difference between the male and female stock of human capital (see graph below). Indeed Goldin contends that the decline in the US gender pay gap to date has been largely due to an increase in the productive human capital of women relative to men.

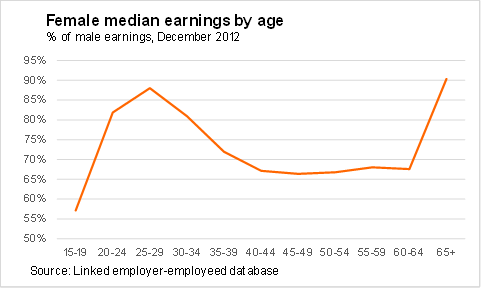

Goldin notes that the other three explanations are unlikely to be major contributing factors as they do not explain some key characteristics of the remaining gender pay gap, at least in the US. For example, they do not explain why earnings differences by sex expand so much with age (a phenomenon also apparent in New Zealand, see graph below). Or why the majority of the current earnings gap in the US comes from earnings differences within occupations rather than between occupations.

We do not have good occupational wage data here in New Zealand so it is difficult to check the extent that within occupation wage differences account for the wage gap in New Zealand. However, in the US it appears that certain occupations impose heavy penalties on employees who want fewer hours and more flexible employment arrangements. Differences in the gender pay gap between occupations appears to be due to the value placed on the hours of work and job continuity of work. Full time workers in some occupations receive far more than twice the earnings of part-time workers who work half the number of hours. That is, in many occupations earnings are not linear with respect to time worked. In occupations where earnings are proportional with the hours worked, the gender gap is low; where there is a premium for working long hours, the gender pay gap is higher.

Goldin notes that in many workplaces, employees meet with clients and accumulate knowledge about them. If an employee is unavailable and communicating the information to another employee is costly, the value of the individual to the firm will decline. Equivalently, employees often gain from interacting with each other in meetings or through random exchanges. If an employee is not around, that individual will be excluded from the information conveyed during these interactions and has lower value unless the information can be fully transferred in a low-cost manner.

Differences in pay arise because of productivity differences in the workplace, not because of inherent differences in human capital across workers. Some workers want the amenity of flexibility or of lower hours and some firms may find it cheaper than others to accommodate this demand.

The job characteristics that seem to be associated with larger gender pay gaps are:

- Time pressure: How often does the job require workers to meet strict deadlines? Lower pressure means workers do not have to be around at particular times.

- Contact with others: How much does the job require workers to be in contact with others (face-to-face, by telephone, or otherwise) in order to perform it? Less contact means greater flexibility.

- Establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships: Developing constructive and cooperative working relationships with others, and maintaining them over time. The more working relationships, the more workers and clients the employee must be around.

- Structured versus unstructured work: To what extent is the job structured for the worker, rather than allowing the worker to determine tasks, priorities, and goals? If the job is highly structured to the worker, the more difficult it is to job share with others.

- Freedom to make decisions: How much decision-making freedom, without supervision, does the job offer? If individual workers determines what each client should receive, rather than being given a specific project, then it is more difficult for clients to be served by workers who do not have an in-depth knowledge of their specific case history.

Goldin found that the relationship is strongest for time pressure, contact with others, and freedom to make decisions, but is also reasonable for establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships and structured versus unstructured work.

The penalty for time out of the labour market also differs greatly by occupation. In an examination of earnings by MBA graduates, Goldin found that after fifteen years, women typically earned 55% of men who graduated at the same time. Three factors were found to explain 84% of the gap. The business relevancy of training prior to MBA receipt, (e.g., finance courses, accounting) accounted for 24% of the gap. Career interruptions and job experience accounted for a further 30%, and differences in weekly hours the remaining 30%. Importantly, about two-thirds of the total penalty from job interruptions is due to taking any time out.

Children are naturally the main contributors to women’s labour supply changes. In the study, women with children work 24% fewer hours per week than men or than women without children – but the difference in earnings is far greater than the difference in hours of work. A flexible schedule often comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, financial, and legal worlds. As Goldin notes, flexibility at work has become a prized benefit but flexibility is of less value if it comes at a high price in terms of earnings.

Where does this leave us? Although I now feel better informed, Goldin’s analysis does not fill me with much optimism that narrowing the gender pay gap is an issue that is readily addressed by public policy. For many occupations, any break in employment can be very harmful to career and earning prospects. Households make labour market decisions that give them the best results as a unit. In a two-person partnership, the decision to have children typically requires one of the partners to have an extended break from the labour market which, depending on their occupation, can have drastic impacts on their future earning prospects. These effects force many households to specialise, with one partner focussing on earning income and the other devoting a greater proportion of time to children and household management.

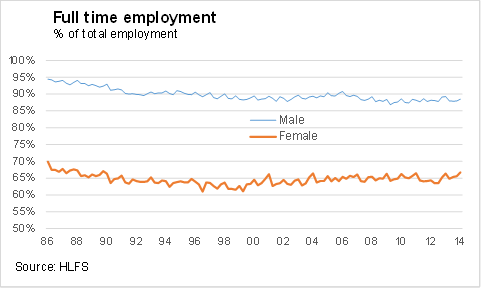

Although there has been a considerable narrowing in the human capital gender gap (see top graph), New Zealand women are still far less likely than men to be engaged in full-time employment (see graph below). To the degree that this outcome represents voluntary choices that optimise the wellbeing of households, the gender pay gap may simply reflect the difficulty in measuring non-market activities. However, this view needs to be balanced against the implications for single-parent households – what might have seemed a reasonable earnings sacrifice in a stable relationship has potential dire consequences should the relationship break down. Specialising household effort between paid employment and household management often makes very good sense, but it is also likely to irreversibly change the bargaining power within the house.