How unequal are our regions?

Over the past year we have heard much about regional inequality, with the term “Zombie town” popping up every few weeks in the media. The debate has contributed to the perception of growing, prospering cities and declining rural areas.

It should come as no surprise that regional inequality exists. The provinces can never attract significant concentrations of the high-paying professional jobs in finance, business services, and telecommunications. We need to accept that incomes in the cities and provincial areas will never be equal.

Although the provinces are unlikely to ever match the cities in terms of the incomes they offer, many provinces have been performing strongly. In an earlier article, my colleague Benje Patterson challenged the notion of regional inequality by comparing growth performance across all territorial authorities. Using the Infometrics regional data base, his analysis shows that the top ten fastest-growing territorial authorities on a GDP per capita basis over the ten years to March 2013 were all in the provincial heartland.

Another angle we can take to understand regional inequality is to compare ourselves to our peer countries in the OECD. How does regional inequality in New Zealand compare with other OECD countries?

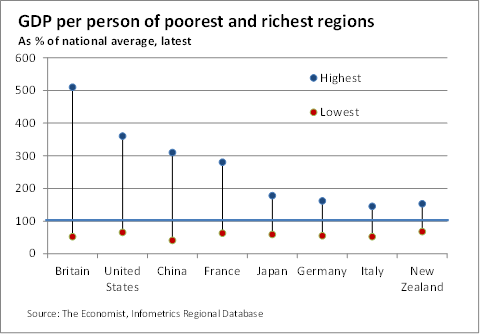

An article in The Economist highlighted the wide gap between rich and poor regions in many developed countries. The Economist correctly points out that regional data comes with health warnings. Comparing regions across countries is difficult due to differences in sizes of regions. The Economist mainly uses the OECD “small areas” of which there are more than 100 in Britain with an average population of about 600,000. These “small areas” are somewhat comparable with New Zealand’s Regional Council Areas, which enables a rough comparison.

By comparison to the countries featured in The Economist article, New Zealand has the lowest level of regional inequality. GDP per head in New Zealand’s wealthiest region is only 2.3 times higher than the poorest region (see the chart below). Britain has the widest disparity, with average GDP per head in central London nearly ten times larger than in parts of Wales. Apart from New Zealand, Italy and Germany have the smallest regional spread, yet GDP per head in their most affluent areas are still almost three times those of the poorest.

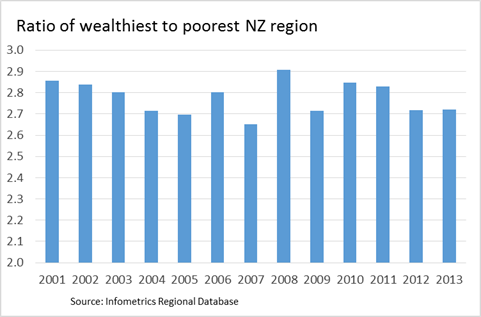

Not only is New Zealand’s regional inequality the lowest among the comparator countries, but it has also been declining over time. Regional inequality peaked during the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and has been on a downward trend since then. In 2001, the highest GDP per head was 2.9 times more than the lowest. By 2013, this ratio had dropped to 2.7.

So why does New Zealand have a narrower regional gap than other OECD countries? Although there are undoubtedly pockets of desperation in the provinces, generally speaking the provinces have performed well economically. New Zealand’s rural areas are supported by a strong agricultural sector and have benefitted from very high productivity growth in the sector. Indeed, over the last 20 years, the agricultural sector has achieved productivity growth only exceeded by the communications industry, the latter being driven by very rapid technological advances in telecommunications.

In contrast to very rapid productivity growth in the agricultural-based rural areas, New Zealand’s cities have struggled relative to their international comparators. Productivity growth in business services, a major contributor to growth in New Zealand’s cities, has been disappointing. Two New Zealand cities have recently fallen out of the top 50 global city rankings. In terms of GDP per capita, Auckland is far behind its comparator cities in the Asia-Pacific region.

New Zealand’s cities lack the scale of the Australian and Asia-Pacific cities and have consequently not been able to sufficiently capitalise on the benefits of agglomeration. New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland, can only compete with second-tier Asia-Pacific cities such as Brisbane and Adelaide, and has lost financial institutions, corporate headquarters, and a number of promising IT firms to Sydney and Melbourne.

A further contributor to low regional disparities is New Zealand’s mobile workforce, which can move from areas of high unemployment to low unemployment, thus evening out unemployment and its contribution to low GDP per capita. There is considerable evidence that Kiwis are highly mobile and move to where the jobs are. Southland experienced some hard economic times during the 1990s and, as a consequence, many of its residents moved out in search of employment in other parts of the country and around the world. Labour mobility has kept its unemployment down and GDP per capita up, despite its below-average economic performance.

Too much has probably been made about regional inequality in New Zealand. Although there are pockets of decline, indeed desperate decline, that need the full attention of policymakers, on the whole our provinces are holding their heads up. We have strong provinces with good economic prospects as the demand for high-quality agricultural products around the world continues to grow.