Why the Living Wage isn’t all it’s cracked up to be

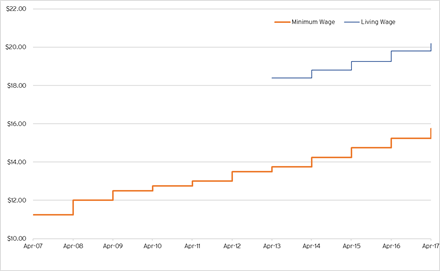

The Living Wage is going up. A month ago, Living Wage Aotearoa announced that from July 2017, the official New Zealand Living Wage will increase by $0.40 to $20.20 per hour.

The Living Wage is heralded as “the income necessary to provide workers and their families with the basic necessities of life. A living wage will enable workers to live with dignity and to participate as active citizens in society.” [1] However, beyond the ideological hype, the following questions remain;

- Does the Living Wage benefit those it seeks to help?

- What is the impact of the Living Wage on the economy and the labour market?

In this article, I examine these questions and conclude that not only does the way the Living Wage is calculated not accurately reflect the reality for families in New Zealand, but that upskilling the workforce may be a better alternative to help those on lower wages.

Does the Living Wage benefit those it seeks to help?

An oversimplified wage…

The rate for the Living Wage is applied nationally, based on the average household of two adults and two children. While the blanket rate means that it is easy for employers to implement, it over-simplifies the New Zealand labour market.

Additionally, as Treasury has already pointed out [2] the assumption of a Living Wage for a two adult, two children household is unrealistic and skews the benefits of the Living Wage; for example, only 6% of families who earn below the Living Wage in 2013 fall into this category.

Figure 1: Changes to the Minimum and Living Wage

…that’s unreflective of actual costs…

Currently, the Living Wage is adjusted based on movements of national wages, rather than on charges in prices and people’s spending behaviour. This year’s update was adjusted by the rise in average ordinary time hourly earnings in the Quarterly Employment Survey (QES) results. The initial calculation of the Living Wage took into account rent, food costs, and household utilities, giving them larger weights than in the CPI as people on lower incomes typically spend a far greater proportion of their wages on these basic necessities than more wealthier households do. As the Living Wage is now adjusted based on labour costs and not expenditure patterns, it is becoming less able to directly represent the earnings level needed to achieve its self-stated goal [3].

… and doesn’t actually benefit those it seeks to help

The Living Wage is intended to help those who struggle to meet costs for the basic necessities – often this will be families. However, compared to families with children, single earners and couples without children (more of whom are earning below the Living Wage) see a larger increase to their purchasing power as a result in of an upward shift in the Living Wage. This lack of income change for families with children comes about due to the higher wage being offset by a reduction in government assistance in the form of Working for Families tax credits and such, resulting in a very similar household income position as before (if not a worse position due to tax creep).

What is the impact of the Living Wage on the economy and labour market?

The Living Wage ignores regional cost differences

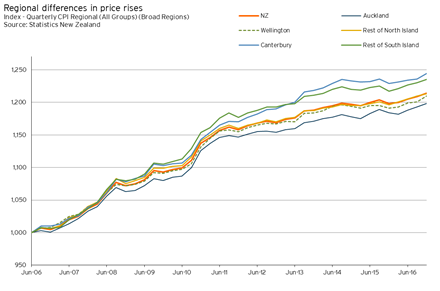

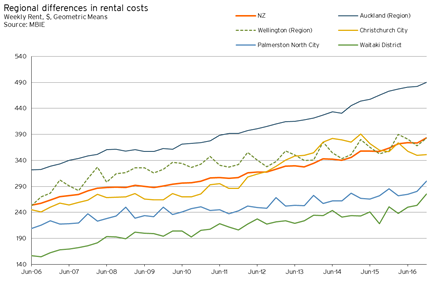

The Living Wage does not consider regional differences in the cost of living. There will be some regions where the Living Wage is overpriced, and others where it is under-priced. The estimated cost of living in Auckland, for example, is far greater than in Dunedin, yet the Living Wage remains the same for both cities.

Not only are there differences between employers’ cost structures (for example the cost of raw materials and transport) and hence how much they can afford to pay in different areas, but regional areas also experience different prices of goods. Statistics New Zealand’s headline regional CPI series provides a broad-strokes view of the differences in price, showing that the relative price of goods and services in different regions has changed across the last few years, while other metrics – such as house prices and rents – provide an absolute cost overview of the regional differences that wage earners are subject to. In short, it is clear that the Living Wage is unable to properly account for regional variation.

Figure 2: Quarterly CPI Regional All Groups (Broad Regions):

Figure 3: Average Rents per week, Selected Regions and Territorial Authorities:

A widespread Living Wage would cost jobs and taxpayers’ money…

It’s obvious that the over simplification of the national Living Wage provides a platform for a less than optimal outcome for families, but what about for the wider economy and businesses? The briefing to the Workplace Relations and Safety Minister for the 2017 [4] and 2016 [5]. Minimum Wage Review gives an indication of what the Living Wage could cost the economy, with these briefings stating that the introduction of the Living Wage on a broad basis would cause an extra 28,000 people to become unemployed, and would cost the taxpayer over $500m for extra service provision.

… while allowing a free ride on productivity

Further to this, implementing a Living Wage would distort pricing signals for labour, with unbalanced incentives in reverse order. By raising wages to be set at the Living Wage rate, productivity change is assumed to occur as a consequence of wage increases, rather than as a reward. This is the opposite of how markets work – increases in productivity are rewarded by higher wages as the higher productivity should (theoretically) increase profit margins, allowing more to be returned to labourers. Instead, under a Living Wage, there is no reason to work to increase productivity, there’s just more being paid for exactly the same outcome.

Where to from here?

More emphasis on differences needed

In the face of rising consumer demand for socially responsible business, the Living Wage is one option a business can look to react with. However, the Living Wage needs to be a good benchmark, specific to businesses’ differences – reflective of where they and their employees work, and who they are. In other words, are they in a provincial or urban area? Are their workers generally families, or younger single workers?

The Living Wage isn’t for every business, and it is recognised that some businesses aren’t able to fund this increased pay rate, or are unwilling to given the reasons outlined above, including a lack of drive for higher productivity.

Even so, some businesses argue that by paying a higher wage rate, you make employees feel more invested in the company and less likely to leave, among other things – in the long-run aiding productivity through lower retraining costs. In this case, if the Living Wage is to act as a guide for labour payment, it needs to work better for businesses, with a recognition of productivity growth, employees’ living costs and regional differences.

An alternative option?

If it is greater productivity and quality of life that businesses are searching for, then I propose that it would be wise to reinvest some of the funds set aside for Living Wage payments into upskilling staff (through training and other professional development). That’s a more sustainable way to benefit both employees and businesses as the approach can help boost worker productivity and give employees a more valuable skill set to see them through life.

——————————————————————————————————

[1] Living Wage Aotearoa. “The Living Wage Rate”.

[2] Treasury. T2013/2346: Analysis of the Proposed $18.40 Living Wage.

[4] Cabinet Paper – Annual Minimum Wage Review 2016.

[5] Cabinet Paper – Annual Minimum Wage Review 2015 and Minimum Wage Order 2016.