Understanding the unemployment problem

The unemployment data over the past year has been especially nasty. Not only has the unemployment rate been rising, but the proportion of the unemployed who have been so for over six months has also climbed. Long-term unemployment is a vexing social issue, which is particularly costly for the individuals affected but also imposes costs for the whole of society. Although it might not be a problem we can necessarily “solve” it is one we should recognise – and an area where we can try to reduce the costs to those affected.

Much has been made about New Zealand’s high unemployment rate; with large groups of people screaming at the government and Reserve Bank that something must be done to get people into jobs – either by shutting off their benefits or “creating jobs”. In truth, unemployment is an unfortunate side-effect of the fact that the world changes through time and that sometimes things go wrong, and no amount of screaming at or about beneficiaries is going to change this. If, as a society, we really want to help those who are struggling we need to actually pick up on who these people are – and why they are suffering.

One of the lessons from the reforms of the 1980’s and early 1990’s was that it wasn’t brief periods of unemployment that caused harm, it was long-term unemployment. In 1987 not only was unemployment low, but the proportion of people unemployed who were out of work for six months or more (long-term unemployed) was only 27%. Following a series of unfortunate events, unemployment rose over 11% by 1991 and a massive 44% of these people were long-term unemployed. Furthermore, this proportion remained above its 1987 level until 2003, as employers were relatively unwilling to take a chance on people who had been out of work for a sustained period of time.

The costs of long-term unemployment

These periods of long-term unemployment come with costs. The most obvious cost is the harm to the individual looking for work – remember someone who is unemployed is saying that they are looking for work and haven’t been able to find it, a situation that extremely disheartening and upsetting.

However, even moving away from the emotive costs, there are cold hard monetary ones as well. When a person is out of work for a considerable amount of time some of the inherent skills they developed (or would have developed) in work will be lost. This deterioration in human capital implies a loss in the value that can be created. Furthermore, employers will be more suspicious of potential employees who have been out of work for a considerable amount of time – making it less likely they would “take a punt” on hiring someone, and if they did they would be less willing to risk using them for certain tasks.

In these ways, long-term unemployment comes with significant personal, social, and economic costs.

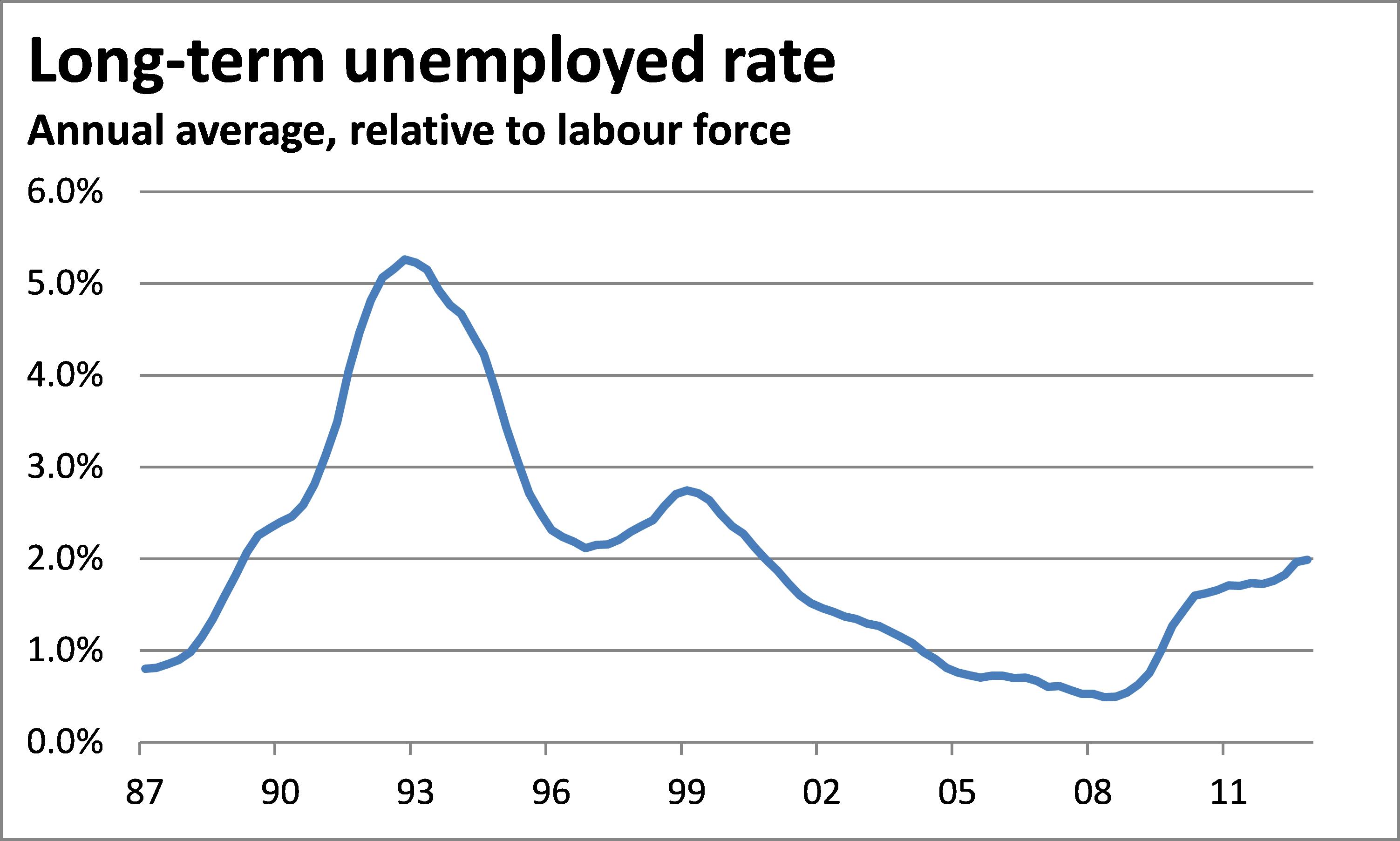

In order to get an idea about where we are now, we can look at what proportion of the labour market has been made up by long-term unemployed people over the last 25 years. Let’s call that the long-term unemployed rate and draw a graph (the data is from Statistics New Zealand):

So how does where we are now fit into this discussion about long-term unemployment? Since the global financial crisis struck, the number of long-term unemployed people has risen. In the 2012 calendar year, the average long-term unemployed rate rose to 2.0%, its highest level since September 2000. Encouragingly, this is still low relative to what New Zealand experienced through the 1990’s, but it is starting to reach a level where we should pay attention.

As we can see from the above graph, the jumps in long term unemployment occurred during recession in New Zealand. Long term unemployment is primarily a problem when the domestic economy slows and firms become unwilling to hire. As a result, far from an indication that people are being lazy and that we should tighten benefit conditions (which at times seems to be the current government’s focus) this is an indication that people are willing to work, but cannot seem to find appropriate jobs either during or in the years following an economic crisis.

A period of elevated long-term unemployment is likely to occur again, irrespective of government policies, with the Reserve Bank reporting that matching in the labour market has deteriorated (http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/research/bulletin/2012_2016/2012Dec75_4cgg.pdf). The way to understand this is to think that there is currently a gap between the skills and abilities potential employees have (both perceived and real) and the skills and abilities the employers require.

Where are these matching problems especially bad?

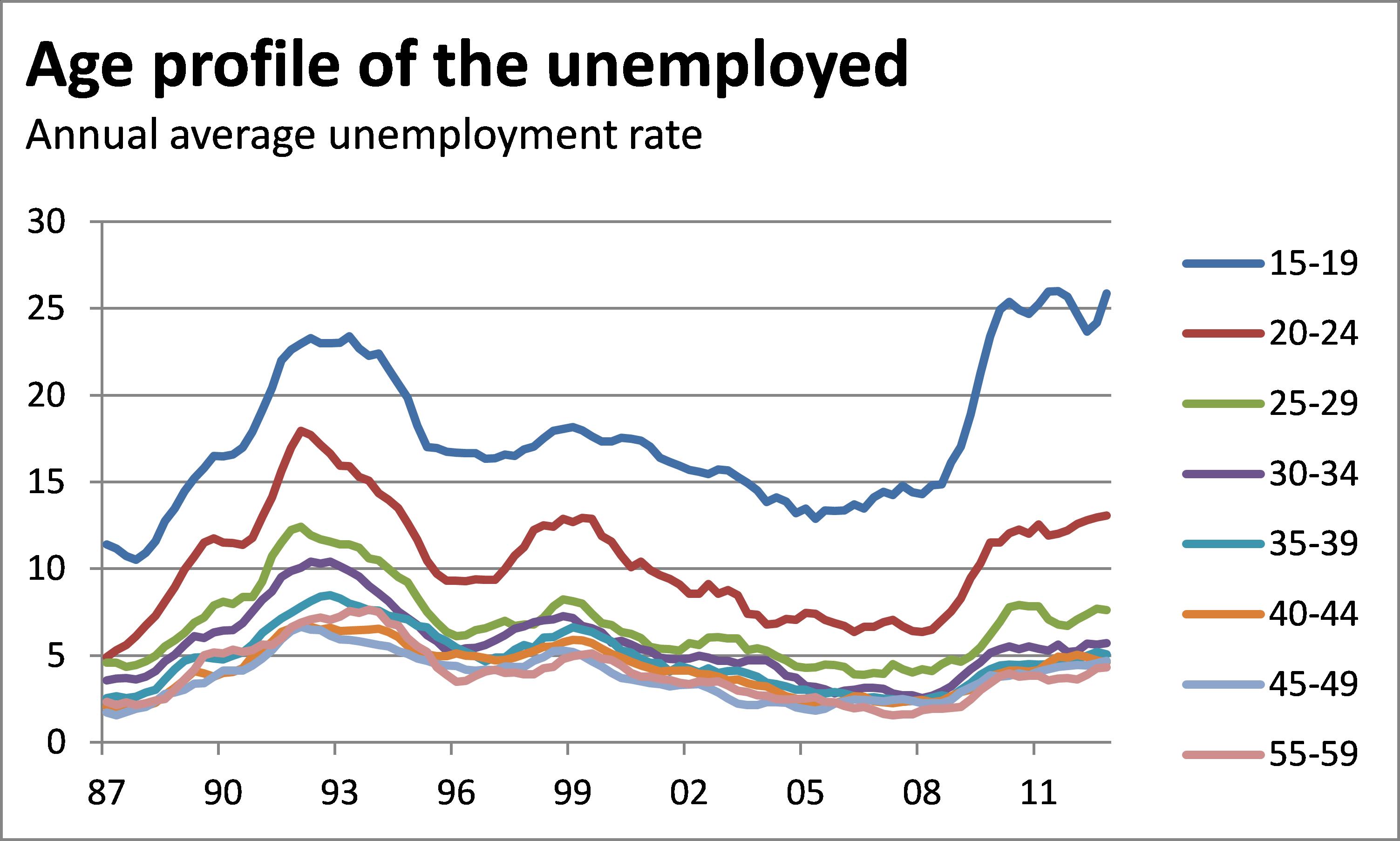

One area where this matching problem is especially concerning, and where this recession is as bad or even worse than the early 1990’s is in the area of youth unemployment.

As we mentioned earlier, one of the big costs for both the individual and society is the loss of skills – or the failure to gain skills – due to unemployment. With the annual average unemployment rate of 15-19 year olds over 25% (and 20-24 year olds facing an unemployment rate of over 13%) there is a significant group of young people who are unable to build up their human capital at present, due to the lack of available work. This reduces their future ability to earn income and to join in as an active member of society.

Given that both of the issues of long-term unemployment and youth unemployment are problems of matching and gaining skills, as a society it may well make sense to help support people when finding their way into work. Furthermore, it would make sense to work with businesses to articulate the skills and abilities they require, giving potential employees some information regarding what sort of training they can, and should, get.

The recent push by the government to boost apprenticeships, combined with the long standing policy of Work and Income New Zealand to help match employees skills to employers requirements are a positive way forward. And following an economic crisis of the size and scope of the one we’ve recently experienced, and the gradual but persistent shrinking of the manufacturing sector, more of these sorts of policies are required to limit the harm for those who find themselves at the wrong end of the labour market.

Right now this isn’t the same sort of national disaster as the problem of long-term unemployment was in the 1990’s. Let’s ensure it doesn’t become one, by focusing on helping people train and find roles that suit them and the demands of employers, rather than concentrating on putting the foot down on beneficiaries.