The necessity of importing skilled labour

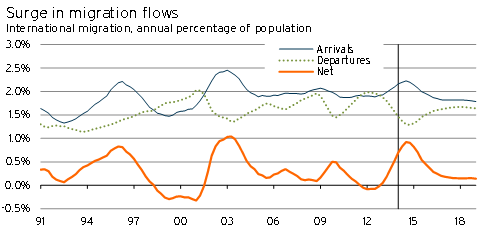

Net migration has climbed sharply over the past year, leading to growing comparisons to the 2002-2004 period. In this article we discuss the ways the current lift in net migration is similar to the previous migration boom, how it is different, and why these differences matter.

Net migration has risen significantly in the past year, with a surge in arrivals and an even larger drop in departures behind the lift.

The increase in net migration has led to increasing anti-immigration rhetoric from political parties and pundits, with migrants being blamed for rising costs, clogged roads, and the upward march of house prices in Auckland.

However, a key element that a lot of this discussion misses is that the higher population growth doesn’t just increase demand for goods, services, and broader development, but also provides capital and labour to help increase the supply. As a result, we need to dig a little deeper to ask what the implications of the current surge in net inflows really means.

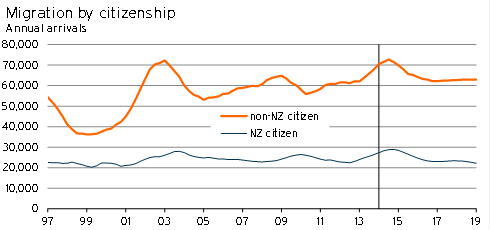

In March, we discussed the departures and arrivals to New Zealand up to that point in detail. Since that time, changes in the flows of New Zealanders have remained the main driver of rising net migration, but rising arrivals from Asia have also had an effect.

Comparing things with 2002-2004

When it comes to thinking about the effect of net migration on inflation and house prices, there is a significant call towards looking at comparing current net migration to the 2002-2004 period.

During 2002-2004, net migration rose far more rapidly than expected. As the lift in net migration surprised forecasters, the Reserve Bank set interest rates too low relative to what ended up being necessary. As a result, inflation climbed and house prices rose at an inconceivably rapid rate.

Graph 5.4

On the face of it, the lift in arrivals and drop back in departures bears some similarity to this period. The net inflow as a percentage of the population is expected to peak at 0.9%, only slightly below its mid-2003 peak of 1.0%.

Furthermore, this lift is due to a rise in the gross flow of arrivals (2.2% of the population, compared to 2.5% in the March 2003 year) and a steep drop in the gross outflow of departures (1.3% of the population, relative to 1.4% in the March 2003 year).

Another similarity stems from the level of non-citizen arrivals as compared to the level of citizen arrivals. The total lift in arrivals of non-citizens is expected to be larger than the lift in the return of New Zealand citizens.

However, the more we dig into the details, the more differences start to crop up between now and the 2002-2004 period.

Graph 5.5

Given that it is the rate of change in arrivals that causes the most disruption, the impulse associated with rising foreign arrivals appears to be smaller than it was at the start of the last housing boom.

Graph 5.6

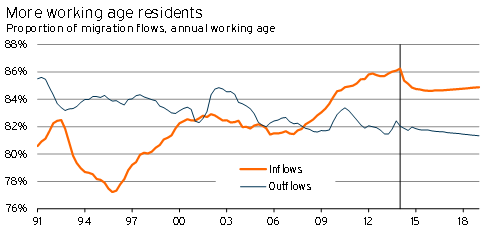

But there is a much deeper change. The flow of individuals moving to and from New Zealand appears to be more centred on increasing the work age population in New Zealand.

During the 1990s there was a lot of talk of a brain drain from New Zealand, as a larger proportion of people leaving New Zealand were of working age compared with people arriving.

Over the 2000s these figures moved closer to matching. Between 2000 and 2010 an average of 82.6% of arrivals were of working age, while 82.8% of departures were of working age.

However, these ten-year averages hide the fact that since 2006/07 there has been a dramatic change. With a growing focus on skilled migration and strong demand for certain labour types due to the Canterbury rebuild, the average proportion of total gross inflows that were of working age in the three years to March 2014 hit 85.9%.

Even with the New Zealand labour market being weak for a long period since the Global Financial Crisis, the proportion of migrant outflows that were of working age eased to 81.9%. In the past year, the proportion of departures made up of people in the 65+ age group rose to 2.4%, the largest proportion since September 1999. With this age group taking up an increasing share of the New Zealand population, it will also take up an increasing share of permanent departures.

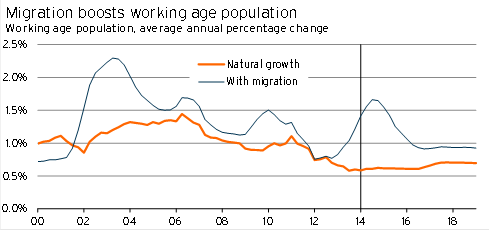

The turnaround in working-age net migration is important for New Zealand, given its effects on working-age population growth.

Graph 5.7

One of the key neglected points in the current debate around migration is the fact that the natural increase in New Zealand’s working-age population has cooled significantly from the early to mid-2000s, and is expected to stay lower. As a result, there is an increasing need for skilled labour to fill this gap in New Zealand, and the implied pressure on building and house prices stemming from growth in the working-age population is weaker.

Visas and the arrival of workers

In its June Monetary Policy Statement, the Reserve Bank pointed out that, compared to the 2002-2004 net migration boom, individuals are coming in on very different visa types at the moment.

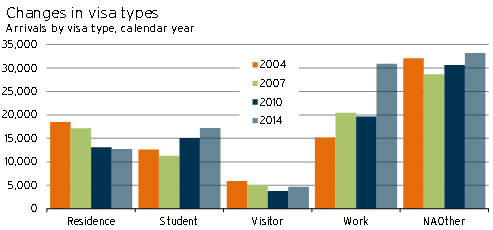

Data from Statistics NZ confirms this assertion. Arrivals by visa type have changed significantly since 2004 (when the data began). In the June 2004 year, residence visas were the key approval category but, by 2014, arrivals on both student and work visas were estimated to be greater than on resident visas.

Furthermore, in the past three years the number of arrivals on work visas has grown at an estimated average rate of 13%pa.

Graph 5.8

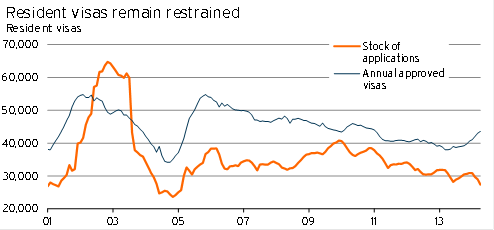

The Immigration NZ numbers give a similar picture with regards to residence and work visas.

Graph 5.9

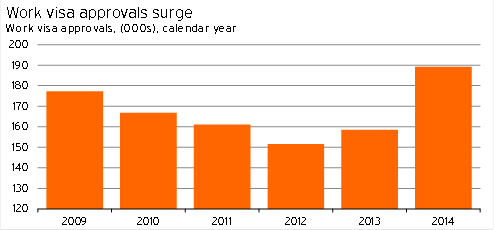

So the figures indicate that the current surge in migration is due to an inflow of workers, rather than simply individuals and families who want to live in New Zealand.

This distinction is important, as the current shortage of skilled workers and demand stemming from the Canterbury rebuild implies that these individuals and families will get more quickly integrated into the New Zealand labour force. As a result, the current surge in net migration will not add to inflationary pressure in the same way as an inflow of individuals who do not have the requisite skills or who are not “in demand” from New Zealand employers.

Graph 5.10

In this way, new migrants are adding essential skills and involving themselves in occupations that will strongly increase “aggregate supply”, thereby creating (in a large part) the goods and services that they demand when they move into the country. This outcome contrasts with the 2002-2004 period, when a much larger proportion of arrivals were coming in on the basis of residence. Some migrants during this previous period will have taken a longer time to integrate themselves into the New Zealand economy and, as a result, they will have pushed up demand pressures.

Furthermore, the fact that the visas are based on work rather than residence implies that the recent lift may be less permanent than the lift experienced in 2002-2004, as people may well head overseas again after the expiration of their work visas.

In this context it is important to keep in mind that people included in Statistics NZ’s “permanent” migrant category aren’t necessarily permanent. All this category implies is that someone has come into the country and is intending to reside here for at least a year!

If many of the permanent arrivals are only intending to be here for 1-3 years, or if arrivals are uncertain about their ability to get residence, this will influence demand patterns by people currently moving over to New Zealand. Instead of driving up demand for housing, and related residential construction, there will instead largely be greater demand for rental properties. Furthermore, purchase patterns will be different, as temporary workers will be less interested in investing in long-term durable products.

Conclusion

The current lift in net migration inflows of skilled, working age, individuals is putting some upward pressure on house prices and will force an increase in the population density of wherever these people move. Furthermore, a faster increase in population growth, due to high net migration inflows, is likely to push the Reserve Bank to lift the official cash rate more than it would have in the absence of these inflows.

However, the migration inflows will also fill an important gap in the labour force, which in turn increases the incomes of New Zealand workers and satisfies the requirements of New Zealand employers and capital owners.

Additionally, the breakdown of visa numbers suggest that the current population flows are relatively temporary. Demand pressures pertaining to current net inflows may be significantly lower than they were during the last peak in net migration between 2002 and 2004.

Even with the current migrant inflows, population growth (especially working-age population growth) is cooling. With fertility rates low and retirement rates picking up, current net migration rates still imply much lower rates of population growth over the next few years.