The migration levels we should be targeting

Infometrics estimates that over the coming decade, net migration of between 10,500 and 16,600pa appears to be appropriate to maintaining New Zealand’s population growth relative to world growth. However, with net migration currently sitting at 72,300pa, a gradual approach to pulling back the numbers means that it could be seven years or longer before net migration sits within this range.

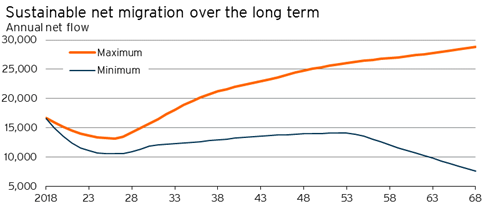

Over a 50-year horizon, the uncertainties around population growth and broader economic conditions increase. Our estimated average for sustainable net migration over this period lies in the 13,100-21,600pa range. This article investigates these aspects in more detail.

Maintaining positive population growth is an important facet of an economy’s performance, at both a national and regional level. For example, an expanding population enables retail businesses to achieve growth without having to rely on each individual customer spending more. However, a shrinking population implies that businesses would need to sell more to each customer over time just to maintain steady revenue. The long-term outcome of this latter trend is for fewer businesses in a town to be viable, reducing the services available to the remaining people, making the town less attractive to live in, and reinforcing the trend of a shrinking population. There are several examples of towns around New Zealand where the population has been stagnant or shrinking for much of the last 30 years, threatening the whole town’s long-term viability.

Arguably, the most problematic aspect of New Zealand’s population growth over the last 20 years has been the significant swings in net migration. A relatively steady rate of population growth allows planners, policymakers, and private sector decision-makers to appropriately plan for the provision of housing, civic infrastructure, and other necessary goods and services. But New Zealand’s population growth has varied between 0.5% and 2.1%pa during both last decade and this decade, making planning decisions that much harder.

Because New Zealand’s immigration policies operate independently from overall population growth, migration flows, if anything, tend to exacerbate the economic cycle. Strong economic conditions in New Zealand, particularly relative to Australia, will encourage fewer New Zealanders to head overseas and more to return home, but are also likely to attract more foreigners here to live and work.

Although migration is not the only cause of the current affordability crisis in the Auckland housing market, the fact that population growth in the region has accelerated so much over the last five years has definitely played a role in the housing market’s imbalances. The response of monetary policy to the housing market has been limited by a lack of inflation throughout the rest of the economy, which has resulted in interest rates being kept low and forcing the Reserve Bank to implement other measures such as loan-to-value restrictions.

But it is easy to envisage a situation where an earlier tightening in immigration policy resulted in labour supply constraints limiting economic growth as well as feeding into greater cost pressures, more inflation, and tighter monetary conditions (which would help reinforce the slowdown in economic growth). Arguably, in this situation, the housing market would have been prevented from becoming as imbalanced as it has, with weaker demand due to slower population growth and higher interest rates.

In our view, overall immigration, along with each of its subcomponents, needs to be considered within the context of targeting a more stable rate of overall population growth. So, when the net outflow of New Zealand and Australian citizens is small (or, as is currently the case, is actually a net inflow), visa approval numbers across the categories that generally contribute to permanent and long-term arrivals could be scaled back. In other words, there would be fewer resident, work, and student visa approvals during times when population growth was already relatively strong due to the net flows of New Zealanders.

One of the obvious questions posed by limiting immigration when there are plenty of job opportunities and the economy is growing strongly is “what about businesses that are already finding labour difficult to come by?” Restricting immigration during these periods would push up wages, encouraging businesses towards more investment in labour-saving technology, thereby improving New Zealand’s labour productivity . The scarcity of workers would also help ensure that labour was directed towards the areas that it was most productive.

During periods of strong demand for workers, the mix of visa approvals could be moved more towards the skilled migrant category, with fewer approvals of student or family visas (which contribute less to the economy’s productive capacity, at least in the short term). Approvals of onshore resident applications could be increased to help maintain a reasonable supply of resident visas, while there could also be scope to allow extra extensions of temporary work visas for people already in New Zealand.

In periods such as the late 1990s, when New Zealand’s weak economic performance contributed to a large outflow of New Zealanders, increased visa approval numbers could have helped to keep population growth at a higher rate, boosting aggregate demand and helping stimulate economic activity. There might be some scope for increasing residence approval numbers, particularly compared with times when overall approval numbers are constrained by the contribution of New Zealander flows to population growth, but there must be caution that the bar for residency is not lowered too far in terms of the skills contribution that immigrants can make to the New Zealand economy.

Instead, the best vehicle for boosting immigration during such a period is likely to be via increased approvals for those people on student and temporary work visas. Although some immigrants in both these categories subsequently apply for residency, people in both groups have a relatively high propensity to leave New Zealand again within three years. Thus, issues of migrant quality, which are particularly important for residence applications and immigrants’ long-term contribution to New Zealand’s workforce, are less critical for migrants that are only here temporarily. This assertion is backed up by the fact that any subsequent residence applications for people here on student or temporary work visas will be assessed on the skills (or other) criteria set down by government policy.

New Zealand’s population growth in a global context

We believe that aiming for a relatively stable rate of population growth should be a central goal of migration policy. In this regard, determining what is an appropriate rate of population growth to target is a second-order issue. Nevertheless, we believe that targeted population growth:

- should not be negative, to prevent the problems associated with a shrinking population

- should not be so strong that it causes undue stresses on the economy, even if the growth rate is stable

- should not be so strong that the quality of immigrants being accepted is detrimental to New Zealand’s overall skill base and long-term potential growth.

The final point hints that the potential supply of migrants wanting to come to New Zealand is an important influence on the appropriate rate of population growth. Anecdotally, New Zealand is relatively high on people’s choice of destination to migrate to, so in theory there should be an almost unlimited supply of potential migrants for us to choose from. However, slowing population growth, both in other developed countries and in developing countries, raises questions about the potential supply of migrants over the longer term.

Slowing population growth, an aging population, and a rising dependency ratio in developed countries suggests that there could be greater competition from other nations to attract skilled migrants over the medium term. At the same time, slowing population growth in developing nations, due to improved access to contraception and rising incomes encouraging more women into the workforce, will mean that the pool of potential migrants wanting to shift to developed countries might not be as large. The latter factor arguably has the most scope over the long-term to undermine the quality of potential migrants looking to move here.

Hanging over the influence of these trends in global population are two other macro developments. Firstly, we have seen suggestions that the falling real cost of travel and rising incomes in developing countries are leading to greater international mobility and, as a result, the trend in net migration to New Zealand will continue to rise over the medium term. In our view, this one-sided projection places too much weight on recent years in estimating the underlying trend in net migration. It also fails to consider increased departure numbers that could result from the growing ease of international travel.

Secondly, there has been increasing discussion in recent months about the rise of automation and the future of work. Although the aging population means that New Zealand’s already-tight labour market is likely to tighten further over the next 4-5 years, it is unclear what the relative demand for labour will look like over a 20-year horizon, as technological advances potentially make a lot of current jobs obsolete. Systemically higher unemployment could conceivably undermine the case for allowing continued migration if those people arriving in the country are not able to support themselves financially.

Graph 19

Keeping in mind the caveats that these possible trends present, we have estimated appropriate levels of net migration based on New Zealand’s population growth relative to projected population growth in high-income countries and total world population growth. Over the coming decade, net migration of between 10,500 and 16,600pa appears to be appropriate given population growth overseas. However, with net migration currently sitting at 72,300, a gradual approach to pulling back the numbers means that it could be seven years or longer before net migration sits within this range.

Over a 50-year horizon, the uncertainties around population growth and broader economic conditions increase. Our estimated average for sustainable net migration over this period lies in the 13,100-21,600pa range. However, slowing population growth in developing countries could limit the supply of appropriately skilled migrants so that a net inflow as low as 7,600pa could be appropriate at the end of the projection period. The upper end of our range by 2068 is a net inflow of 28,900 people per annum – a figure that, given the expansion in New Zealand’s population over the next 50 years, is equivalent to a net inflow of 20,500 people per annum now.

This article was part of an in-depth report on migration. Please find the full report here.